J. Cameron Fraser

Reviewed by: Gregory E. Reynolds

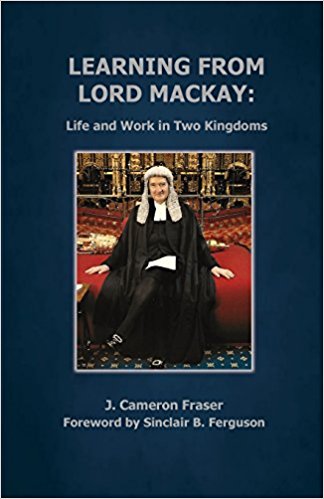

Learning from Lord Mackay: Life and Work in Two Kingdoms, by J. Cameron Fraser. SoS-Books, 2017. Paperback, 128 pages, $12.00. Reviewed by OP pastor Gregory E. Reynolds.

This is an unusual book written by Cameron Fraser, once the editor of the Presbyterian Guardian. The book explores the sterling character of Lord Mackay and how he navigated the two kingdoms of his British context.

The subtitle of the book, “Life and Work in Two Kingdoms,” is of special interest to Orthodox Presbyterians, as Fraser notes in his preface (7). He begins with Melville’s famous humiliation of King James VI, when he reminded the king that he was merely a member of the Church of Scotland (11). Fraser traces the development of the two kingdom doctrine through Luther, Knox, and Calvin, concluding with the enshrinement of many of their ideas in various Reformed confessions (12–17).

While the structures of establishment exist in England, “pluralism and secular values … hold sway. How is a Christian in the tradition of the Westminster Confession to conduct himself in such a context?” (20). Enter the story of Lord Mackay, one time Lord Chancellor of the British government, who outranks even the Prime Minister.

Mackay was raised in the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland, in which his father was an elder (25). After graduating from Trinity College, Cambridge, he went on to practice law in Scotland. In 1979 Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher appointed him Lord Advocate of Scotland, “the chief legal officer of the government and crown in Scotland” (30–31). Then in 1987, Thatcher appointed him as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain (34–35).

Fraser emphasizes the effect Mackay’s Christian character had on his legal associations. “Lord Mackay has become known in the legal profession, in political circles and the media as well as in the church, for his unassuming humility, personal loyalty, and gracious character” (58). This character was cultivated by faithful Lord’s Day observance (61).

In favoring no-fault divorce law, Mackay parted company with many Christians and conservatives. He believed that the acrimony created by the necessity of finding fault was damaging to the children and the couple (67, 105). His ideal was marriage between a male and a female for lifetime (106).

Fraser locates Mackay’s position on the two kingdoms in the contemporary context. Fraser quotes with approval from Tim Keller’s 2012 book Center Church, which provides a helpful summary of the weaknesses of both the transformationalist and the two kingdom positions (84–89). One of Keller’s criticisms of the two kingdom position raises a good point that has always intrigued me. “Much of the social good that Two Kingdom people attribute to natural revelation is really the fruit of the introduction of Christian teaching—special revelation if you will—into world culture” (86). I doubt that many two kingdom advocates would disagree with the reality of this influence. I certainly don’t.

According to Fraser, Mackay

does not self-consciously operate on the basis of either model. But his concern for personal godliness coupled with his realistic view of what can be accomplished in a fallen political system seem to me to place him closer to the two kingdoms model. (93–94)

The discussion of the relationship between church and state will no doubt continue until the end of time. This book makes a nice contribution to the conversation. More importantly it provides an inspiring example of a Christian serving in church and state.

December 07, 2025

November 30, 2025

November 23, 2025

November 16, 2025

November 09, 2025

November 02, 2025

October 26, 2025

© 2025 The Orthodox Presbyterian Church